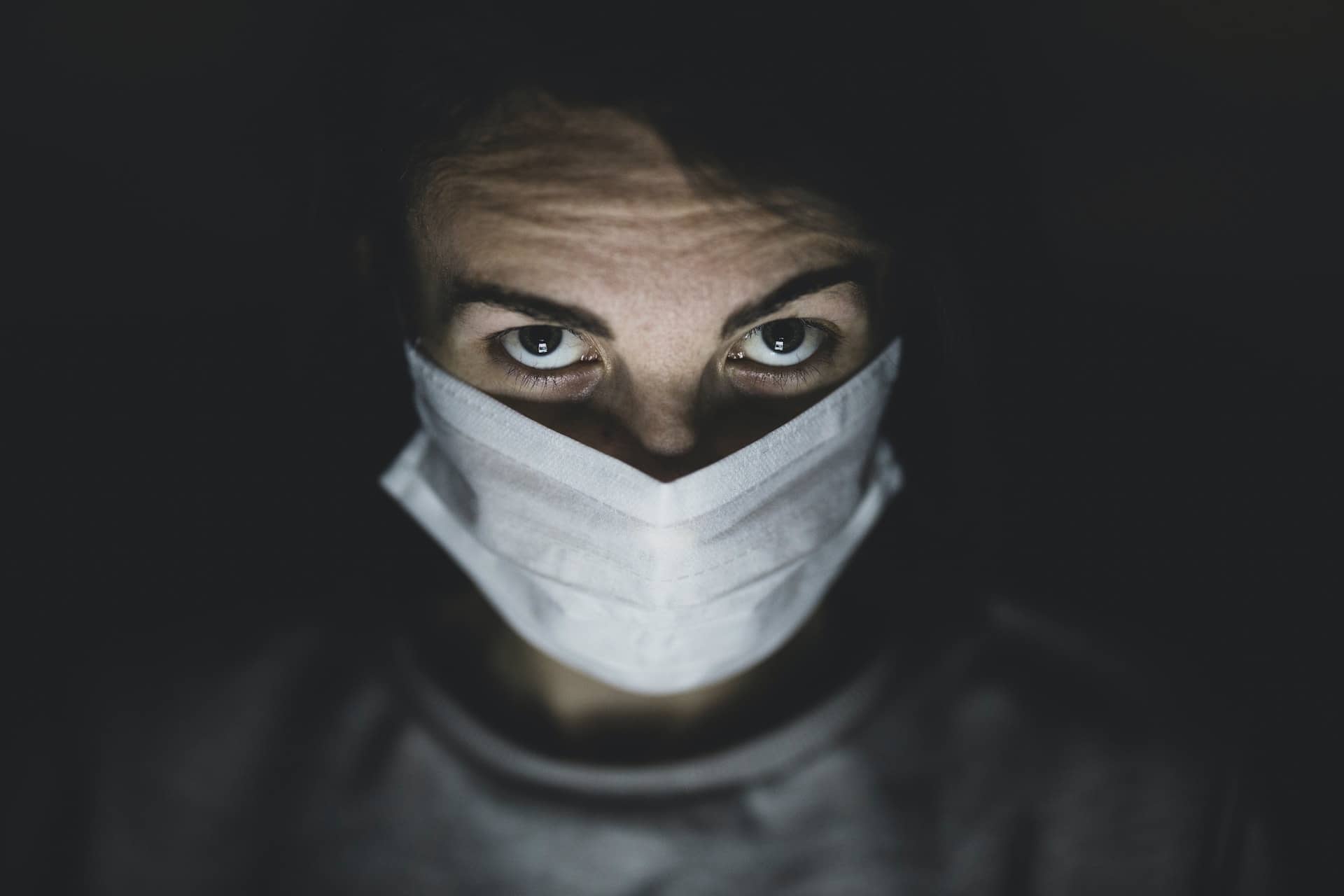

As the number of COVID-19 cases surges, and death rates continue to rise, anxiety is escalating. Kluger’s recent piece in Time, “The Coronavirus Pandemic May Be Causing an Anxiety Pandemic,” depicts the proliferation of new and recurring anxiety conditions as tensions heighten. Vox’s “How to Manage Anxiety During a Pandemic” offers practical advice on ways to cope with the fear of infection and other related stressors, including unemployment. Further, the increased usage of online therapy apps in recent weeks suggests the acute need for access to mental health resources in order to address the psychological and emotional reactions to the current crisis.

Unfortunately, this upturn of anxiety is not limited to the fear of being infected or of a loved one dying.

Instead, psychological reactions to COVID-19 are triggering a range of other, previously dormant, emotional dilemmas, awakening other areas of concern that, ’til now, have existed only in the background.

The social isolation, loneliness, and fears naturally associated with life during pandemic are aggravating other unresolved issues existing long before the onset of COVID-19: the lingering distrust of one’s partner, long-held resentment toward a family member, dissatisfaction and restlessness with one’s career. In the stay-at-home atmosphere when the usual routine comes to a sudden halt and there is simply more time for reflection and self-examination, the problems we have compartmentalized, or distracted ourselves from, naturally come to the fore.

Yet, at still another level, the recent demand for mental health resources and psychotherapy appears to be related to the pandemic far more tangentially than one might suspect.

Anxiety, and its core elements of vulnerability and fragility, are more akin to a labyrinth rather than a singular structure such as a tumor. These components reside in the mind as a constellation of interrelated sources of apprehension, distress, and unrest woven together in a complex psychological entanglement. When one area of fear, worry, or concern is activated (like coping with a pandemic), it likely will activate others. As a result, one obvious source of trepidation (COVID-19) may psychologically uproot another that has lingered in the recesses of one’s mind, unrecognized and undisturbed, for years or even decades.

This was Freud’s conceptualization of anxiety and it remains a compelling perspective on psychic suffering. For Freud, mental phenomena are inextricably linked, both in origin and expression; they are bounded and mutually determined.

Freud’s notion of “screen memory,” for example, emphasized the tendency of the unconscious to adjoin memories and events for defensive purposes, ultimately obfuscating reality. In contemporary literature, perhaps no better example of a screen memory exists than Anthony Hecht’s “A Hill,” a poem in which two distinct scenes — a piazza in Italy and a hill in Poughkeepsie, New York — encountered at two different times in the speaker’s life, are mysteriously intermixed.

Although Freud theorized about a range of psychiatric conditions, anxiety remained a primary interest throughout his career. Freud argued that anxiety was more of a signal rather than a psychiatric problem in and of itself; when it occurred, “signal anxiety” pointed toward the formation of a deeper, more turbulent storm in the psyche, an unconscious subterranean conflict in which an evolving idea, feeling, or memory could not be tolerated and, consequently, needed to be suppressed or resisted.

Implicit in Freud’s view is the assumption that the experience of anxiety always suggests an underlying conflict, unresolved memory, or emotional strain, and without this more troubling issue there would be no anxiety. What this means is that any situation which triggers anxiety can also impel less obvious, and often more painful, dilemmas.

A colleague of mine once presented a case at a conference in which his patient, a 35-year-old woman who lost her mother to cancer four months earlier, was suddenly overcome by a flurry of severe episodes of anxiety that ultimately met psychiatric criteria for panic attacks. What was determined in the course of this woman’s psychotherapy was that the death of her mother stimulated within her the unbearable thought that she, too, could die imminently, thus abandoning her own children. In one particular session, this woman was shocked by her realization that when she had become a mother, she must have relinquished her own mortality without even knowing it.

It may be of no surprise to learn that that is not where this woman’s work ended.

Anxiety about abandoning her children with her own death gradually unveiled a link to yet another source of anxiety residing behind the screen of her contemporary preoccupations. Early in her childhood she suffered rheumatic fever and, for several weeks, had been unable to walk. In therapy she recalled that when she was first diagnosed and bedridden, her fear of her illness and anxiety about her fate became so intense and unbearable that she plainly recalled wanting to die rather being courageous, the latter of which her father had been urging her to do. All her life, trying experiences that called for a hunkering down, or a pushing through against all odds, had always tripped her up in one way or another.

The pandemic is activating in each of us not only obvious fears, but the deepest unresolved issues that occupy our minds and hearts. Our fears and trepidations are linked in ways that are out of our awareness, but still very real.

0 Comments